|

Greeks first settled on the Greek mainland about 2000 B.C. Geography played a

large part in the formation of their society, as it does in all civilizations.

Mountain ranges divide Greece into many small valleys. The resulting pattern of

settlement, so different from that of Egypt, encouraged the Greeks to develop

independent political communities without the direction—or oppression—of a

central ruler. The broken coastline, indented with countless small harbors,

invited the people to become sailors, traders, and warriors at sea. By 1600 enterprises by sea had transformed a number of the independent

Greek communities into wealthy, fortified states. Chief among them was Mycenae;

therefore the years from 1600 to 1100 B.C. are often called the Mycenaean Age.

Two sets of graves found in the soil of Mycenae have

given us a fascinating glimpse of the wealth and

artistic accomplishments of this city. The graves in

each were enclosed within a circular wall. The older

set, tentatively dated between 1700 and 1600 B.C., was

outside the walls that surround the citadel of Mycenae.

Interred there were wealthy Greeks, perhaps from a royal

family or clan. Alongside the bodies, the surviving

relatives had deposited various offerings, for example,

a golden rattle in a child's grave. The second set of

graves, inside the citadel walls, far surpassed the

older ones in wealth. |

|

These graves, dated between 1600 and 1500 B.C., were

discovered in 1876 by one of the founders of Greek

archaeology, Heinrich Schliemann, and are still among the

wonders of archaeology. Their contents include such

stunning luxuries as three masks of gold foil that were

pressed on the faces of the dead and a complete burial

suit of gold foil wrapped around a child, as well as

swords, knives, daggers, and hundreds of gold

ornaments. Bulls' heads in the graves indicate the

influence of Crete on artists working in Greece.

The graves tell us little about the political or social history of Mycenae, but

they do demonstrate its growing wealth in the sixteenth century. The city's king

was probably its chief religious officer as well as commander of the army.

Elaborate fortifications and large numbers of swords and other weapons at

Mycenae and other early Greek cities indicate that Greece was a more warlike

society than Crete.

The economic organization of cities in the Mycenaean age resembled that of

Oriental kingdoms in its centralized, "vertical" system. This is shown by the

contents of Linear B tablets, written in the same kind of early Greek that was

used at Knossos, that have emerged from the soil at Mycenae, Thebes, and Pylos.

The largest group, that from Pylos, can be dated soon after 1200 from the

evidence of pottery

fragments found with them. The tablets themselves are preserved only because

they were baked in fire as these several cities were destroyed by invaders. All

the tablets are rosters and inventories, cataloguing oil, seed, objects of

metal, men, and women, all in the service of the palace bureaucracy.

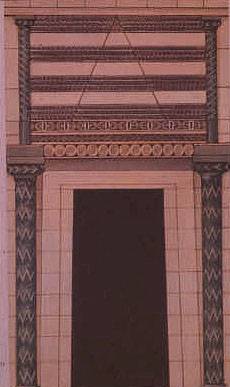

Between 1400 and 1200, Mycenae reached the height of its prosperity and created

the most imposing monuments in all Bronze Age Greece. Between 1350 and 1300 the

stupendous walls around the citadel were built in their present form; it is

significant that such defenses were apparently needed, as they were not (or at

least none was built) on Crete. The mighty Gate of the Lionesses (or Lion Gate)

was erected as an entrance to the city, and the most expensive Mycenaean tombs

were built. These are the beehive-shaped, or tholos, tombs, large vaults with

walled entranceways. The grandest and best preserved is the so-called Treasury

of Atreus, conventionally named for the legendary father of King Agamemnon—but

we do not really know which rulers were buried here. The high vaulted ceiling is

still intact, and the somber cavern creates a breathtaking effect.

Each city of the Mycenaean period was probably independent under its own king.

The only time these cities appear to have united was during the war against

Troy, a prosperous city in Asia Minor near the Dardanelles. The origin of the

Trojans is not yet clear, but some of their pottery suggest a close relationship

to the Greeks. Apparently the Trojans were rich and offered a tempting prospect

to pirates and looters. This was probably the real cause of the Trojan War, but

ultimately Greeks explained the origins of the war by the romantic story in

Homer's Iliad about the seduction by a Trojan of Helen, the wife of the king of

Sparta. The excavation of Troy, begun by Schliemann at Hissarlik in Turkey, has

disclosed several layers of building. One layer, called Troy VII A, was

destroyed by an enemy about 1250. This evidence suggests that Homer's account of

a successful Greek expedition against Troy contains some historical truth.

The war against Troy was the last feat of the Mycenaean Age. About 1300 or a

little later, various marauders began to attack Greek ships and even mainland

Greece. The identity of these warriors is still uncertain. Historians usually

call them sea-peoples, and their homes were probably somewhere in Asia Minor.

Whoever they were, they made trading by sea so dangerous that the export of

Mycenaean pottery virtually ended. The raids by sea were temporarily

destructive. But much more significant was a series of attacks by land, lasting

roughly from 1200 to 1100. Near 1100, Mycenae itself was overrun and destroyed.

It is still not wholly clear who these land invaders were. Ancient Greek

tradition spoke of the "return of the sons of Heracles," by which was meant the

supposed return of Greeks speaking the Doric dialect of Greek to their ancestral

home in the Peloponnese; the same traditions worked out a date for this event,

which we can equate with about 1100 B.C. But we cannot accept such material from

sagas without question, and this "Dorian invasion" has been debated from the

beginning of the modern study of Greek history. In an attempt to replace the

traditional view, that the speakers of Doric Greek were roughly the last wave of

Greeks to arrive in Greece, some historians have suggested that all the Greek

dialects arrived more or less at once. Only later, they think, after a social

revolution of some kind, did the speakers of non-Doric dialects in the

Peloponnese take flight to other regions, thus allowing the Doric dialect to

emerge in linguistic documents.

This is possible, but the traditional view can also be defended and seems

preferable on balance. Mycenaean civilization suffered a series of shocks, and

when we have evidence about Sparta and other sites in the Peloponnese we find

many of them occupied by speakers of Doric Greek. Sparta in fact became the most

important of the Dorian states after the Dorian invasion had run its course.

The period from 1100 to 800 B.C. is known as the Dark Age of Greece. Throughout

the area there are signs of a sharp cultural decline. Some sites, formerly

inhabited, were now abandoned. Pottery was much less elegant; burials were made

without expensive ornaments; and the construction of massive buildings came to a

halt. Even the art of writing in Linear B vanished. The palace-centered

bureaucracies no longer existed, but of the political machinery that replaced

them we know almost nothing.

Still, the cultural decline was not quite a cultural break. Farming, weaving,

and other technological skills survived; pottery, though it was for a while much

less gracious, revived and developed the so-called Geometric style. Nor was the

Greek language submerged. Many Greeks, displaced from their homes, found safety

by settling in other parts of Greece.

In a larger sense, the shattering of the monarchic pattern in the Mycenaean Age

can be viewed as a liberating and constructive event. We cannot show that the

kings and dynasties in Greece were dependent on or were imitating kings in the

ancient Near East, but the two systems of monarchy resembled each other. If the

Mycenaean kings had survived, mainland Greece might have developed as Anatolia

did, with strong monarchies and priests who inter preted and refined religious

thought in ways that would justify the divine right of kings. Self-government

within Greek states might not have emerged for centuries if it appeared at all.

But the invasions of the twelfth century, in which the Dorians at least played a

part, ended forever the domination of the palace-centered kings.

|